Back in 2018, I was woefully unfit. I hadn’t exercised in years and I was not paying my diet any better attention. I, like anyone else who is or has been in those shoes, was well aware — intellectually — about what it might take to make those things less true. But that knowledge felt insurmountable. There was no joy in doing those things: running on the treadmill when I hated it, eating a depressing salad that felt more like self-punishment and restriction than self-actualization and reward.

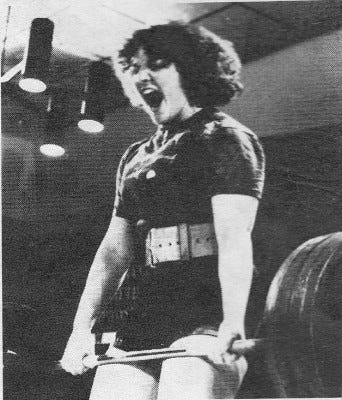

It was really through the encouragement of a small minority of friends who resonated with where I was at that a barbell made it into my hands. And it felt good. Something about the additive nature of weightlifting — adding weight — clicked for me. I was always focused on losing weight but here was an area where there was permission to do the opposite — to add weight.

After a few more years of switching between lifting, conditioning, and yoga, I made the choice, two years ago, to fully double down on lifting. I embraced lifting maximalism — choosing to specialize and go deep in one sport versus trying to be the well-rounded, “generalist” athlete.

This was a departure from my usual mode of being. Everywhere else in life, I am the “jill of all trades.” I specifically made the choice, in college, to transfer to a liberal arts school where I didn’t have to declare a major and could live out the dreams of my interdisciplinary heart. Like other music hipsters, my tastes are “eclectic,” drawing from sounds across the East and the West, past and the current.

But in the gym, my interests are barbell-heavy.

When I tell people today — who don’t lift themselves — that I lift weights, 3 times a week, for two to three hours at a time, during set days of the week, they often feel impressed. But then I can see something else, deeper within them, that resists it.

Often it’s something like how lifting is not for them. They don’t think they could ever do such a thing. Where I am today feels like a mountain they could never scale. And occasionally there’s that harsh judgment — that powerlifting is only for fat people or people who hate cardio and lack flexibility.

Look, powerlifting is not a perfect approach to fitness. But it’s not bad either. It’s something — it’s my form of exercise. The only type that I’ve so far been so called towards. It gets me in the gym. It gets my heart rate up. It makes me feel better about myself to make progress, week after week.

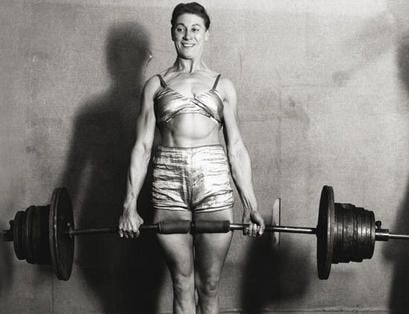

I’m going beyond my expectations for myself. I remember when I thought a woman benching 95lb was impressive. It had felt impossible to me. Recently I set a lifetime PR of 145lbs.

Unlocking goals that are distinct and measurable in the way that the weights on a barbell can be added up has done numbers for my self-esteem.

Maximalism gets a bad rep. You’re choosing to focus exclusively on one thing over everything else. You’re missing out. You’re not prioritizing balance. You’re going to get injured.

There’s some truth to those criticisms. But what about the benefits of maximalism?

Maximalism gives you focus. It reduces complexity and choice. When I go to the gym to lift, I have a specific program that I follow that day. I am accountable to both myself and my coach. I know that I need to be adding weight to the bar, week after week. I know exactly what I’m doing. I’m completely dialed in.

Maximalism also helps you find your people. Lifting connects me to others who have found love in this sport, the same way marathon runners connect.

It doesn’t mean that the maximalists in the other sports are bad. I instead prefer the sentiment behind the Burning Man phrase “fuck your burn.” To the uninitiated, “fuck your burn” sounds pretty rude. It’s an eff-you after all. But within the Burning Man community, it’s an honest shorthand for something more like “hey, that’s not for me, but I totally respect that it is for you!”

So it’s okay if powerlifting is simply not your burn. But don’t try to take the virtues of my maximalism away from me.

So what happens when you do max out? When you reach your body’s limit and are incapable of squeezing out another PR? Does the “myth” of maximalism’s appeal get dispelled once you reach your ceiling?

I like to take a broader view. I think that the ceiling itself is a myth or a red herring.

First, it’s unlikely that the regular person — even if they lift 3x a week under the guidance of a coach and so on, like myself — will easily max out. It took me about 2-3 years into lifting for me to discover the concept of “lifetime intermediate.”

The lifetime intermediate is someone who gets sick sometimes. They sometimes get injured. They go on vacation. Sometimes something big and disruptive happens in their life, whether it’s getting laid off or getting hired for their dream job.

The lifetime intermediate is a mere mortal like you and me. Life naturally programs deloads. Maximalism is not perfectly linear.

So I’ve learned to see the bigger picture. My setbacks force me to dig deep for patience. I’ve had to learn to enjoy the process of becoming as much as I enjoy the payoff — the PRs at the end.

But yes — powerlifting is a sport that’s fundamentally about maxing out within your gender, weight, and age brackets.

When I consider this, I think about my coaches experienced competitive powerlifters with state records under their belts. I even think about my friend Chelsea, an elite powerlifter with an international gold medal in the bench press. Chelsea is literally world-class and breaking ceilings.

These lifters are still chasing maxes, but they’re all invested in passing their wisdom down to others. They enjoy the community aspects of lifting and want to give back. I think there comes a point in an elite athlete’s career where they “retire” from chasing their highs. But they sublimate their expertise — their maximalism — into other pathways to fulfillment.

One of my coaches is a meet director, recently bought and opened her gym, and also ran for state chair within her powerlifting division. She’s using powerlifting to deepen her career, become a business owner, and give back to the community of powerlifting.

Chelsea put a successful consulting career on pause to currently pursue a master's program in nutrition at Columbia University. She says that having to constantly cut and bulk weight to meet the powerlifting weight classes — as well as her journey with body image and muscle building — has disposed her to better understanding others’ diet struggles. She wants to make an impact here.

Finding your maximalism can open the door to so much more.

In its ideal form, maximalism becomes the doorway to the infinite from the finite. You can find breadth even when you’re deep in something. It can lead to self-actualization along multiple dimensions: health, social, career, moral, and spiritual.

In my own training, I’ve learned that volume work is the foundation on which heavy singles are built. And anyone who has done volume work, especially in a lift like squats, knows that they’re taxing. They’re cardio.

So I’m working with my coaches to find ways to weave in some cardio conditioning into my workouts. So far I most enjoy picking up heavy sandbags over a yoke, every minute on the minute. It’s cardio disguised as a strength workout. I’m working on being more well-rounded, just through the door of my maximalism.

This is just one area where I’m trying to broaden through my maximalism. But I know that there is a whole lifetime’s worth to explore here. I’m not just interested in playing the finite game of powerlifting. I want to use it as a gateway to exploring more: cardio, cooking, lifting, and coaching. I can’t do all those things at once. But I fortunately have the years ahead of me for that.

This type of maximalism is what I call healthy maximalism. It goes beyond the ceiling myth. I’ve not lost sight of the fact that cardiovascular health is important. But I’m going to use the now stable, passioned love I have for lifting as a stepping stone for getting there.

So how can you find your own maximalism?

For me, it was addressing that big nagging question that was bugging me in 2018: how do I become less horribly unfit?

Instead of going for the obvious answers that I knew everyone else would provide, I leaned into something that would get me close to that but was not exact — I leaned into what felt good, even if it felt like cheating. I leaned into lifting even if it first meant choosing strength at the exclusion of cardio or mobility.

When it comes to fitness, lifting is my strength. I found a strength of mine in a domain where I was once completely weak. And now I’m going to use that strength as a foundation to continue to grow and deepen.

This is the beauty of allowing yourself to like something for your own, personal reasons. The reasons that aren’t perfectly rational. The reasons that aren’t intellectual or befit to someone else’s talents or values.

What if some of the wisdom to getting started with the difficult — the insurmountable — lies in carving out a space within it for your own maximalism?

Thanks to all my friends and coaches who have helped me with my lifting along the way. Also thanks to Camilo Moreno-Salamanca, Garrett Kincaid, and David Perell for their help as this piece was published through Write of Passage’s Writing Sprint.

This really got me thinking. Great writing and a compelling concept — what is "balance" anyway?